Though Rand Fishkin famously co-founded Moz and starred in its Whiteboard Friday video series, it’s hard to rule out the possibility that he’s cursed.

Back in 2008, Moz had its first big software launch the same day Lehman Brothers collapsed. “The literal day,” Fishkin told Built In.

Now, 12 years later, Fishkin is launching a new product during the shelter-in-place phase of the coronavirus pandemic.

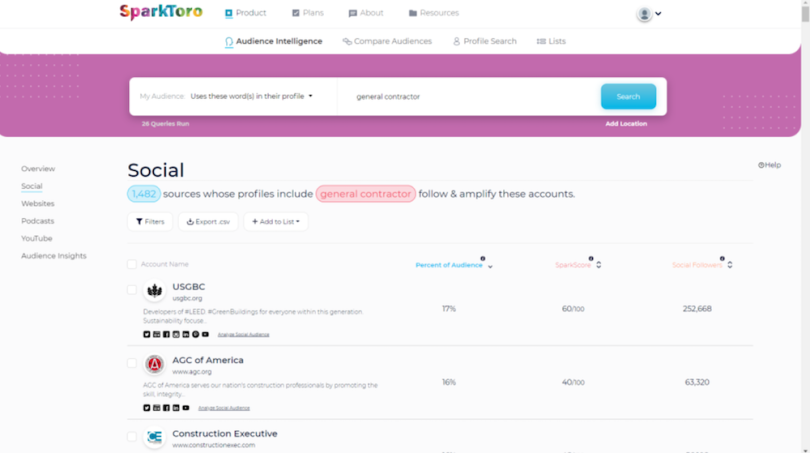

That product is SparkToro, an audience intelligence tool. Marketers search for the demographic they want to reach — whether that’s architects, CFOs at Seattle-based SaaS companies, or people who frequently talk about The Bachelor — and SparkToro returns a list of the podcasts and YouTube channels they like, the websites they visit, and the social accounts they follow.

The underlying goal: To help marketers forge direct relationships with influencers and ad-supported media outlets, without Facebook or Google brokering the relationship.

“We think it sucks that so much of web marketing today is ‘buy ads on Facebook and Google.’”

“We think it sucks that so much of web marketing today is ‘buy ads on Facebook and Google,’” Fishkin and SparkToro’s CTO and co-founder, Casey Henry, wrote in the company’s vision statement. “That duopoly makes marketing less creative, less interesting and less fruitful.”

Facebook and Google require ads to fit a hyper-specific specific format, and can be “incredibly expensive” for small businesses hoping to reach in-demand audiences, Fishkin said.

SparkToro isn’t the first market research tool to tackle this issue, but it’s one of the first accessibly priced ones. Historically, enterprises have spent hundreds of thousands of dollars to build tools like this in house, Fishkin said. Small businesses can’t afford that. SparkToro costs orders of magnitude less, though — even the priciest subscription, for unlimited searches for up to 50 users, costs under $500 a month.

The tool also relies exclusively on public social data. Rather than relying on third-party cookies, it tracks who reads which websites through implicit logic: If someone shares a link to a website on social media, they probably read it. This makes SparkToro well-positioned for the decline of third-party cookies.

It could have all added up to a straightforward launch.

“What make SparkToro so great?” Fishkin joke-pitched. “It exists.”

The pandemic adds some complexity to the situation, though.

From Frustrated Blogger to the Wizard of Moz

Complexity isn’t new to Fishkin. He started his marketing career exploring the subtleties of one of the most complex algorithms in the world: Google’s search algorithm.

Updated hundreds of times a year, this algorithm helps Google connect users with relevant information. It also allocates a firehose of web traffic; Google gets nearly six billion queries per day, and sites its algorithm perceives as “relevant” see huge numbers of search-referred visitors. However, the algorithm’s definition of relevance remains shrouded in mystery.

Google offers some guidance on SEO best practices, but an entire tech vertical has also risen up to refine, automate and add to those best practices. SEO currently has its own suite of specialized software, from companies like Moz and SEMRush; a host of consultants and online courses; and a controversial black-hat sector.

Back when Fishkin was starting his career in the early aughts, though, SEO resources were sparse and expensive. He had dropped out of college to work with his mom, Gillian Muessigi, on her marketing business, then called Outlines West, and he realized that, if they were going to offer clients SEO services — as they had promised to — they couldn’t afford to contract out for it. Fishkin would have to learn to do it himself.

“I probably was reluctant until my mom showed me the bank account,” Fishkin said. “We were in pretty bad financial shape.”

SEO was confusing, though. Fishkin began blogging about his frustrations with it, and the insights he was able to piece together. That blog built a brand for Outlines West, which became Moz. The blog, which had great SEO when you Googled “SEO,” became a launch pad for bigger things.

By the time Moz launched its first software product, “we already had this audience who had been reading my blog for years at [that] point, who knew [and] ... trusted us,” Fishkin explained.

These core loyalists bought the software, even as the 2008 financial crisis unspooled. Moz raised a first round of venture capital totaling $18 million.

All told, Fishkin stayed at the company for more than a decade, holding positions including CEO and the so-called “Wizard of Moz,” a title his wife Geraldine DeRuiter invented for him. (She also thought of the title of his most recent memoir about his time at Moz, Lost and Founder, in “maybe 30 seconds,” Fishkin said.)

While he was there, a new type of complexity emerged in his work. Google’s algorithm was complicated, but Fishkin’s feelings about SEO grew complicated too.

Doubting Google and Growth

“In my early years at Moz,” Fishkin said, “[I] viewed Google as this wonderful company that was bringing knowledge and information to all of us.” He thought Google stuck to its unofficial, now-abandoned motto, “Don’t be evil.”

Over the years, though, he grew more critical. He wasn’t alone. Employees leaving the company, too, reported a shift.

“The Google I was passionate about was a technology company that empowered its employees to innovate,” wrote James Whitaker, a former director of engineering at Google who left the company in 2012. “The Google I left was an advertising company with a single corporate-mandated focus.”

This cultural shift, in Fishkin’s view, corresponded with a change in how Google treated website owners and content creators.

“[For] a long time, the exchange of value there was, I thought, fair. You produce all this content, you do a great job of optimizing it.... And Google will reward you with traffic.”

“They are the free labor on which Google extracts all of its value,” Fishkin said. “And for a long time, the exchange of value there was, I thought, fair. You produce all this content, you do a great job of optimizing it [for Google’s search algorithms].... And Google will reward you with traffic.”

Over the past six or seven years, though, Fishkin said that Google has moved toward more exploitative practices: “Google basically said: ‘Oh, you created that content for us. That’s really nice. You’re a real sucker.’”

Google will sometimes, for instance, display website content directly in the search results page, in boxes called “featured snippets,” so that even highly relevant websites see less traffic.

Genius, the lyrics annotation site, has sued Google over the practice, and The Outline reported that it nearly tanked a website called CelebrityNetWorth.com. Fishkin began to question the value of building clients’ reliance on Google, when it could backfire spectacularly.

Around the same time, a new trend was emerging in, or at least near, marketing: growth hacking. First coined in 2010, the term took off among tech startup founders. It was shorthand for budget-friendly, innovative and scalable marketing tactics; often, these involved close collaboration between marketing, product and engineering.

SEO fell under the umbrella of “growth hacking”; it can involve technical tasks like redesigning a site’s architecture and streamlining its URLs as well as content creation.

But Fishkin wasn’t a fan. He saw it as Silicon Valley’s attempt to “masculinize the concept of marketing.” To venture capitalists and founders, growth hacking was about “exploits,” “crushing numbers,” and not doing what expensive, out-of-touch marketers would do.

“I really, really disliked that terminology,” Fishkin said, “and the inherent presumption ... that they were somehow inventing this subculture of marketing.” Sure, new technology had emerged that allowed for new marketing strategies — but it wasn’t a brand new field. “When you look at growth marketing or growth hacking, you kind of stare and say, ‘Boy, that sounds really familiar.’”

Yet growth marketers often position their field as a smarter alternative to marketing — a more efficient, techier version of it that unifies everyone working on a product’s sales funnel around the same measurable goals.

Fishkin doesn’t see it that way. Clearly. Though he’s still chairman of Moz’s board of directors, he’s moved out of SEO and growth marketing to work on a pure, top-of-the-funnel marketing project. SparkToro helps companies connect with their desired audience — not increase their active monthly users, as many growth teams yearn to do.

But why launch SparkToro during a pandemic?

To Launch or Not to Launch

SparkToro needs revenue, like everyone else. But this week’s launch isn’t purely about revenue, or Fishkin and Henry would have stuck to their original launch date, back in March. Instead, they postponed to April.

A March launch “would not have been reading in the room,” Fishkin said. “There was just no oxygen for anything but health issues, economic recovery issues, mitigating disaster issues, helping people in the healthcare and essential workers fields.”

At the beginning of April, he wrote a blog post called “Reading the Room,” where he elaborated:

The world — the whole world — is experiencing this crisis all together. When you send a tweet, write an email, publish a blog post, run a webinar, broadcast or amplify anything right now, you’re sending that message within the context of the Coronavirus outbreak. I’d estimate we have (at minimum) another month where nothing in our lives exists without the filter of the viral crisis and the pains and restrictions it inflicts.

When he and Henry postponed their launch, they didn’t expect public conversation to return to “normal” by April. But they hoped that, by their launch date, people would be paying attention to topics besides coronavirus deaths.

That shift has already begun. After a dip, Fishkin said, traffic has returned to sites like IndieHackers and Product Hunt. “A ton of people are thinking about how they keep their online businesses going and humming.”

So he and Henry decided to launch SparkToro. The mood of the launch has shifted, though.

“Our language and tone is a little less ‘rah rah rah,’” Fishkin explained. “It just doesn’t feel atmospherically correct.”

In the process, they’ve modified SparkToro’s value proposition. Rather than calling it “revolutionary,” Fishkin said, their message is closer to, “we want to help small businesses, media outlets, people who built audiences” recoup some of the revenue they’ve lost due to cratering ad prices.

It’s not pure rhetoric, either. SparkToro has put its money where its mouth is, and made its free plan more generous. Without paying, businesses can run up to 10 searches per month.

Ultimately, though, “we got lucky with SparkToro,” Fishkin said. It’s a digital tool, easily used during shelter in place. It also helps solve a pandemic-related problem. As people pivot their businesses away from events and in-person sales, they need to find audiences for their revamped products.

“It’s not like we’re making personal protective equipment,” Fishkin is quick to note. “But we are still seeing more demand.”

He advises companies considering product launches right now to look at demand too. Does the audience want the product right now? He recommends looking at signals like popular Twitter conversations, Google Trends data, and trade publication coverage. If a product seems relevant in our strange new world, launch it.

“I don’t think that artificially restricting our innovation and entrepreneurship is necessarily a good thing,” he said.

Tone, though, is key. “There’s certain positioning that is crisis aware, but tone deaf,” Fishkin said. He sees it especially in sales materials, in language about “exploiting” this moment while everyone’s stuck at home.

Better to focus on helping suffering customers, he said — in sales rhetoric and in actual business decisions. Though Fishkin’s career has been somewhat non-linear, this has been a through-line: a focus on helping customers, especially small businesses, access once-inaccessible strategic resources.

He likes to see entrepreneurs “build small, profitable, successful, sustainable companies.” It’s personal — after all, that’s what Moz was, after it was deeply in debt and before it brought in tens of millions in revenue each year. It’s what Fishkin hopes SparkToro becomes too.